Behind the Book: Chanchal Dadlani

By Bethany Leggett

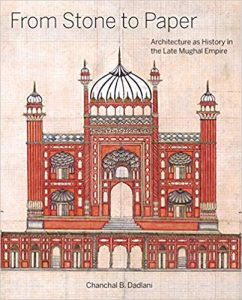

Chanchal Dadlani’s book, From Stone to Paper: Architecture as History in the Late Mughal Empire, looks at the cross section of architecture and history in the 18th Century, an overlooked period of time of the Mughal Empire. It has recently been selected as one of four finalists for the 2020 Charles Rufus Morey Book Award by the College Art Association, with the winner selected later this month.

Dadlani recently spoke with the Dean’s Office about the origins of the book and being selected as a Morey Award finalist.

What intrigued you about this time period of the Mughal Empire that first spurred your scholarship to examine its culture through the lens of architecture?

I have always been awestruck by the grand monuments that the Mughals left behind — most notably, the Taj Mahal. But when I was doing my fieldwork in Delhi — once the capital of the Mughal empire — the city started to intrigue me in a different way. Being on the ground, and experiencing the fabric of the city firsthand, I was drawn to more intimate, less monumental spaces, such as popular shrines, neighborhood mosques, lush gardens, bustling bazaars, and even abandoned mansions that I stumbled across as I explored the old Mughal city. The spaces and places that fascinated me the most, that seemed to me to be the most vibrant and novel, dated from the 18th century, the so-called “decline” period of the empire. I became inspired to explore this seemingly paradoxical relationship between architectural dynamism and political loss.

Was there a wealth of primary documentation waiting for you to build the narrative from?

Yes and no! The first step was to survey and document what I encountered in the field, building my own extensive “architectural archive.” While searching for 18th century building plans, I came across stunning architectural representations — urban panoramas, manuscript paintings, archival maps — but I had to hunt through a number of collections, from municipal records offices in Delhi to colonial archives in London and Paris. I also realized that for textual sources, I needed to reach beyond standard court histories and look to poetry and travel narratives, which offered perspective on matters such as city life and aesthetic sensibilities. And one of the biggest challenges of the project was also one of its greatest rewards: wrestling with sources in Persian and Urdu as well as in European languages.

What were some of the themes or impressions the Mughals wanted to maintain or exert with architecture during this time?

The book takes place during the critical transition from Mughal to British rule in India. While the Mughals experienced dramatic political losses at this time, amazingly, they managed to retain the throne. One of the ways they did this was by using architecture to recall their illustrious past. They built new structures that quoted past masterpieces, or commissioned manuscript paintings portraying historical Mughal monuments. As a result, the Mughals retained their cultural authority, and in the process, they created the very idea of an architectural style that could be identified as Mughal, a style with powerful historical associations.

Is there a bespoke architectural element that you discovered or that surprised you in your research; or is there a particular building that exemplifies the Mughal Empire that you’ve included in the book?

One of the major monuments discussed in the book, the tomb of Safdar Jang, has been famously called the “last flicker in the lamp of Mughal architecture.” In other words, this building was often described in terms of imperial decline. My first encounter with the building, which sits in a large walled garden, took place on a late December afternoon. Winter sunlight illuminated its white marble dome; the surrounding garden offered a quiet respite from the busy city; and the structure featured a series of intricate, beautiful vaults. This experience was one of many that convinced me to write a new story about architecture at the close of the Mughal empire.

What does this recognition of being on the shortlist for the 2020 Charles Rufus Morey Book Award mean to you as a teacher-scholar?

I’m incredibly honored that my book has been shortlisted for the Charles Rufus Morey Book Award. In my writing and teaching, I strive to animate the past, to examine how knowledge is produced, and to emphasize the role of the visual in the narratives that we write about ourselves and our collective histories. Being shortlisted for the Morey Award is a gratifying acknowledgment of these endeavors. In addition, since the Morey Award encompasses the entire discipline of art history, it’s also significant to me that a book on Islamic and South Asian architecture has received this recognition.

What do you enjoy about the work that the College Art Association does?

The College Art Association has been an invaluable resource for me. CAA performs important advocacy work for the profession; publishes one of my discipline’s flagship journals; and, of course, sponsors the annual CAA conference, which is always a forum for the lively exchange of ideas.