Teacher-Scholar Legacies: David Lubin

Wake Forest University faculty, staff, students and guests attended “Looking Closer at American Art A Symposium in Honor of David Lubin” at Reynolda House Museum of American Art on Saturday, April 26, 2025.

The event included presentations, a panel discussion, and a reception in the gardens. Read more at Wake Forest News.

View photos from the event.

By Jay Curley, Professor of Art History

When Professor David Lubin found himself on sabbatical in London in 1998, the British Film Institute approached him to contribute to their new “modern classics” series, inviting him to write about a film of his choosing. During his conversation with the editor, David playfully suggested Titanic, the recently released cultural phenomenon captivating millions of viewers worldwide. When the editor dismissively laughed, David, by his own admission, “changed course faster than the ill-fated ocean liner was able to do.” He launched into an impassioned defense of the film’s scholarly merit, arguing that its portrayal of a vessel on troubled waters brilliantly captured broader social anxieties on the verge of the millennium. The book was published the following year.

This anecdote perfectly encapsulates David’s distinctive approach to art history: a fearless scholar unconstrained by disciplinary conventions. Whether authoring a serious scholarly work on a film many deemed unworthy of such attention, or daring to reframe iconic masterpieces of art through an interpretation of a seemingly inconsequential detail, David has consistently charted his own course beyond established boundaries.

Among David Lubin’s impressive catalog of eight books — five published during his Wake Forest tenure — his 2003 work Shooting Kennedy: JFK and the Culture of Images stands as the quintessential example of his boundary-breaking academic approach. This landmark study delves into the profound cultural significance of iconic photographs of John and Jacqueline Kennedy by masterfully positioning them within an expansive visual network encompassing films, television programs, and classical paintings. With remarkable insight, Lubin reveals how certain images — such as the president at his inauguration — simultaneously evoke ancient Roman statuary and moments from the film Citizen Kane. This dissection of images not only explains how they signified politically and propagandistically, but also serves as a primer for how art history can explain the complexities of the visual world. The book’s daring approach was recognized with the prestigious Charles C. Eldredge Prize in 2004, celebrating outstanding scholarship in American art.

His experiences as a young man forged the iconoclastic spirit found in his scholarship. His journey to academia followed an unconventional route: studying film at the University of Southern California, writing for Rolling Stone magazine (after cold-calling the reviews editor and candidly critiquing the magazine’s writing), and moving to Paris, where he immersed himself in the city’s fabled cinema culture. In Paris, he met his future wife, Libby, and together they dreamed of opening an eclectic bookstore-café-record shop on the Left Bank. As a pragmatic backup plan — suggested by his mother — David also applied to Yale’s American Studies Ph.D. program. A faculty member at Yale later revealed that the department occasionally admitted a “wild card” candidate lacking traditional credentials, and David had been selected for one of these coveted positions, his iconoclastic spirit finding an unexpected home in academia.

American Studies, especially at Yale, is a discipline that deliberately blurs traditional boundaries between high and low culture and between academic departments. His dissertation and first book, Act of Portrayal (Yale University Press, 1986), boldly bridged disciplines by analyzing “portraiture” across mediums, comparing painters John Singer Sargent and Thomas Eakins with author Henry James. This approach defied categorization as either art history or literary criticism; it was simply David Lubin, challenging conventional academic boundaries from the start. After Yale, David quickly found an academic home at Colby College in Maine, a small liberal arts college where he discovered the joys of undergraduate teaching.

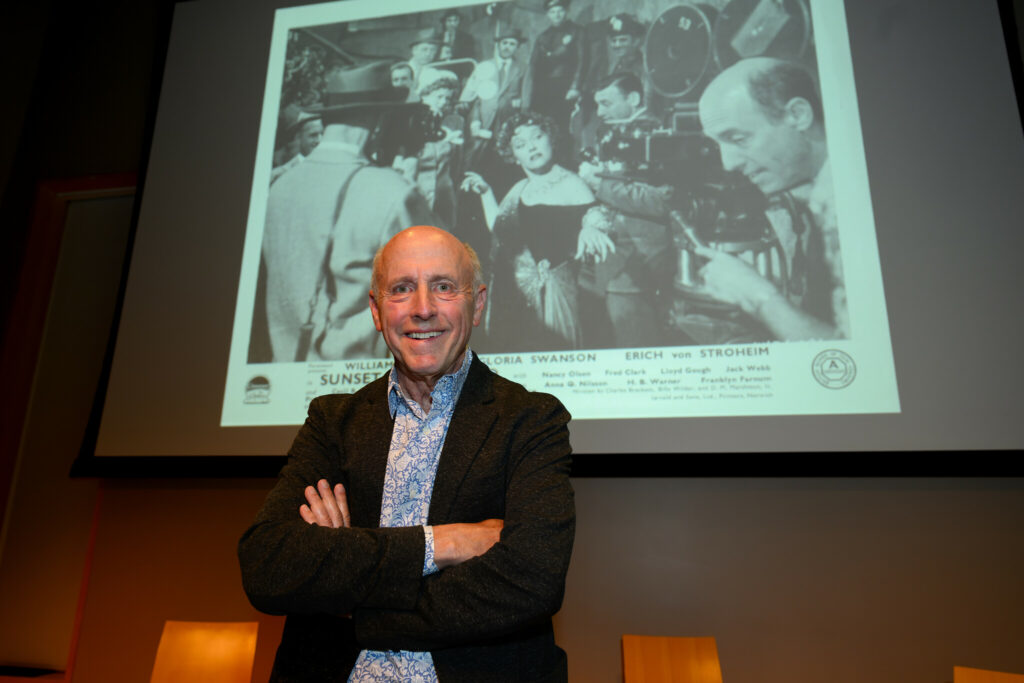

David’s books emerged at a steady pace. His landmark 1994 work Picturing a Nation, with its six chapters exploring different nineteenth-century subjects, revolutionized American Art History through bold contextual interpretations of both canonical figures and lesser-known artists. Following this achievement, the aforementioned Titanic appeared in 1999, precisely when Wake Forest was seeking its inaugural Charlotte C. Weber Professor of Art. The University successfully recruited this scholar who had so profoundly revitalized the study of American art. Defying expectations that an academic of his caliber would gravitate toward an institution with a graduate program, David arrived in Winston-Salem in 1999 and continued his groundbreaking scholarly trajectory, writing Shooting Kennedy, Grand Illusions: American Art and the First World War (2016), and Ready for My Closeup: The Making of Sunset Boulevard and the Dark Side of the Hollywood Dream, set to be released this October.

His many academic endeavors have been supported by prestigious fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Gallery of Art, Harvard University, and the Guggenheim Foundation. As the inaugural Terra Foundation Visiting Professor of American Art at Oxford University, he extended his intellectual influence across the Atlantic. Beyond his publications, David has elevated Wake Forest’s academic reputation through his expansive service to the field, co-curating landmark exhibitions and delivering compelling lectures at renowned institutions throughout the world.

As befitting a Wake Forest teacher-scholar, David’s pedagogy at Wake Forest is legendary. In both intimate seminars and larger classes, he masterfully employs extended class discussions centered on individual artworks as his signature pedagogical method. Through David’s deliberate practice of “slow looking,” images and film clips gradually unveil their profound layers. Graduating senior Avery Houck captures the essence of Lubin’s approach: “Class was never clinical; Professor Lubin never told us what to see in works. Instead, he fostered an open engagement and dialogue amongst students that allowed works to reveal themselves in real time.” Rather than passively absorbing information, students become active participants in a genuine voyage of discovery during each class session. The profound impact of this teaching philosophy extends beyond the classroom walls. Sarah Comegeno (’21) found her life’s direction forever altered during her first year in David’s classroom, remembering, “I realized this was where I needed to be, not the organic chemistry lab.”

As David Lubin retires from Wake Forest, he leaves a dual legacy: scholarship that fundamentally reframed how individuals understand American visual culture, and generations of students equipped with the ability to see beyond the obvious. His approach reminds us that scholarly innovation often comes from crossing boundaries — between high and low culture, between disciplines, and between the classroom and the wider world.