Humanist in Residence

By Alex Abrams

What could first-year Engineering students learn from Raphael’s sixteenth-century painting The Marriage of the Virgin? Or Leonardo da Vinci’s sketch of a self-propelled cart?

Monique O’Connell is a historian, not an engineer. As Professor and Chair of Wake Forest University’s Department of History, she is more familiar with Renaissance politics than the tensile strength of stone.

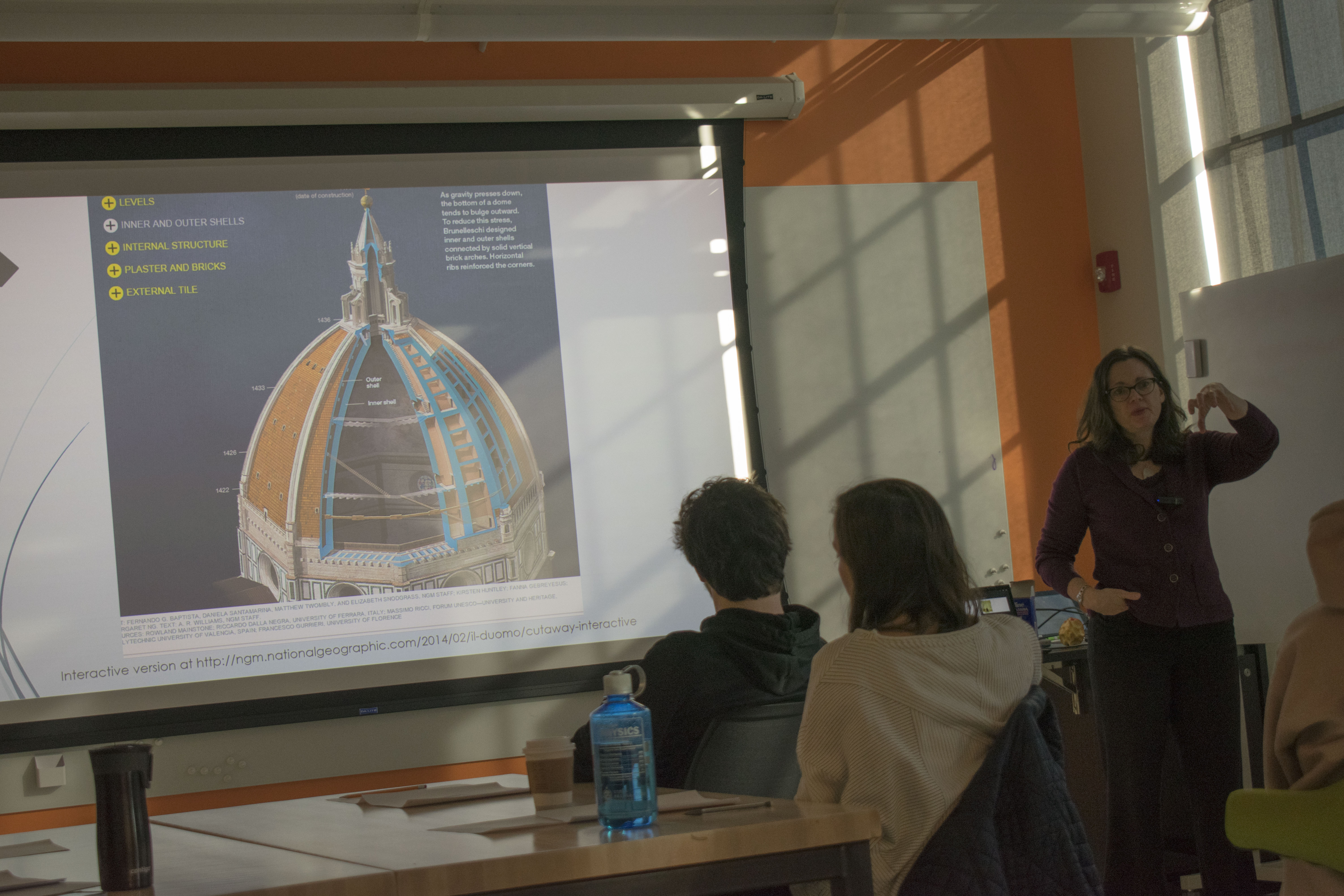

However, standing in a fourth-floor classroom at Wake Downtown, O’Connell talked to a dozen students enrolled in EGR 111: Introduction to Engineering Thinking and Practice about the connections between da Vinci and modern engineering methods.

With her blend of humor and vast knowledge, O’Connell spoke to Assistant Professor of Engineering Kyle Luthy’s class about “Engineering before Engineers.” She shared stories about seventeenth-century British scientist Robert Hooke, who was known for his exact measurements, and she described the ingenuity that sprang from Italian artist Filippo Brunelleschi’s rivalry with Lorenzo Ghiberti.

“My hope is that students are able to see that what I’m talking about is connected to the kinds of problems that they’re going to confront in their careers as engineers and that they’re never going to be able to go into a situation and just do some math.”

Monique O’Connell, Department Chair and Professor of History

Now in its second year, WFU’s Department of Engineering has distinguished itself from other Engineering programs by integrating a liberal arts education into its curriculum.

With that mission in mind – and after several conversations between the History and Engineering departments that started with the two department chairs – it made sense for O’Connell to provide guest lectures as Engineering’s first Humanist in Residence.

This is a part-time position that Wake Forest College created with funding from an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation grant.

“There are all kinds of humanists who can add immense value to an Engineering education,” said Olga Pierrakos, Professor and Founding Chair of the Department of Engineering. “For somebody like Monique who has historical knowledge around a period of time in our history that spurred the beginnings of Engineering and that everyone understands to be a time of revolution, a time of exploration, a time of intense growth, how did people achieve that?”

O’Connell was the ideal faculty member to serve in Spring 2019 as Humanist in Residence. She had been wanting for several years to teach a course on Engineering during the Renaissance.

O’Connell was the ideal faculty member to serve in Spring 2019 as Humanist in Residence. She had been wanting for several years to teach a course on Engineering during the Renaissance.

She also has a particular interest in the history of science, as evident by one of her courses entitled Science, Magic, and Alchemy in Europe, 1400-1700.

“I think that it is really interesting to have students with different perspectives on the material,” O’Connell said. “I had half science majors of various stripes and then half History majors.

“Some of the things that we did were to look at a set of documents or look at a problem and have the students speak from their disciplinary perspectives. I found that fascinating as a teacher to watch them claim their own expertise in a field.”

Naturally, O’Connell had to share her vision with the Engineering faculty on why, for example, a lecture about da Vinci’s unsuccessful attempt to redirect the flow of the Arno River in Italy could teach students about how Engineering systems fail.

It was not a hard sell, though. The Engineering faculty has worked since the beginning of the program to reimagine an Engineering education in context of the liberal arts.

After listening in class as O’Connell described the personalities, accomplishments, and career failures of da Vinci, Brunelleschi, and Hooke, Luthy built stronger connections to modern Engineering practices. He also shared the similarities and differences that shaped the Engineering profession of today.

“Dr. O’Connell’s discussion on ‘Engineering before Engineers’ highlighted how much of Engineering as we know it today was developed in the arts or was born of a social need,” Luthy said. “She not only presented their Engineering achievements but commented on how their character and interpersonal skills influenced their contributions.

“While not technical in nature, these lessons are still very much relevant in Engineering today.”

O’Connell has designed six modules that are being taught across several Engineering courses during the Spring 2019 semester. The modules rely on O’Connell’s knowledge of Renaissance history to address modern Engineering issues. To prepare them, she attended an Engineering faculty meeting in November 2018 and then the department’s curriculum retreat one month later.

During the meetings, O’Connell learned about the different projects the Engineering professors would assign their students and the case studies they planned to discuss in their classes. She then pitched her ideas about how her historical research could be beneficial to the Engineering department, such as with its Materials and Mechanics course.

“After the retreat, I went to the faculty in that class and said, ‘Hey, there’s a great example of a cathedral falling down,’” O’Connell said. “I think that could be used to think about theorizing materials and the tensile strength of stone, which is all I know about that topic.

“But I do know that the Cathedral of Beauvais [in France] collapsed and Engineering scholars are still working on understanding why.”

Pierrakos said she can see the value in Engineering students also learning from other humanists, social scientists, and artists whose research includes such fields as Psychology, Sociology, Anthropology, and the Arts. After all, Engineering involves more than just mathematics and science. Engineering is a liberal art.

Engineering addresses human behavior and human intentions, which O’Connell has conveyed with her talks about da Vinci’s “flying machine” and Hooke’s air pump from 1660.

“She helps us think about the critical point now that Engineering as a profession is going through a transformation,” Pierrakos said. “I think many professions are being challenged to rethink how we educate the next generation of whatever, whether it’s scientists, humanists, artists, social scientists, chemists, biologists, engineers, or medical doctors.”